Hands-on research for undergrads: a lasting legacy from Richard Eisenberg

Jeffrey Weinfeld ’16 said his experience as an Eisenberg Research Fellow this summer taught him a lot about forming a literature search, designing his own experiment, and drawing conclusions from it. Even preparing his poster was a “great experience” he’ll be able to draw on in the future. He worked on “Monte Carlo Simulation of Hard Spheres” under the mentorship of Profs. Shaw Chen and Mitchell Anthmatten.

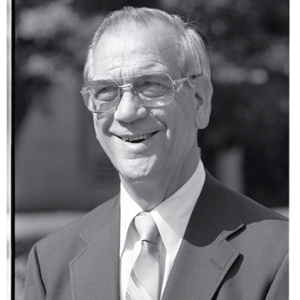

The late Richard Eisenberg, a distinguished University of Rochester professor of metallurgical engineering for nearly 50 years, remembered all too well the work study programs he participated in before arriving at the University as a student in the 1940s. Although financially rewarding, the programs did not relate to his studies and , from a purely educational standpoint, were a waste of time.

The late Richard Eisenberg, a distinguished University of Rochester professor of metallurgical engineering for nearly 50 years, remembered all too well the work study programs he participated in before arriving at the University as a student in the 1940s. Although financially rewarding, the programs did not relate to his studies and , from a purely educational standpoint, were a waste of time.

Thanks to a generous gift from Eisenberg, selected undergraduates in the Department of Chemical Engineering have just the opposite experience each summer before their junior or senior years, working one on one with faculty members on research projects as part of the Eisenberg Summer Internship Program. The program gives students hands-on experience applying the engineering principles they’ve learned in the classroom. It also provides an additional way for faculty to explore new research topics.

From its inception in 1992, students have praised the program for giving them research experiences that they could never obtain in the classroom.

“We can use our skills in ways we didn’t know we could before,” said Natalie Skirko, one of the first students to participate in the program.

Last summer, Branden Cole ‘16 had a similar experience, working with Assistant Professor Wyatt Tenhaeff on materials for a safer lithium ion battery. “In organic chemistry class, for example, you learn how a reaction happens,” Cole said . “But there’s so much more that goes into it. It’s not just mixing this chemical with that chemical. You need the correct conditions, and there are so many outside factors that come into play. It’s all about understanding the process beyond what you learn in class--making it work, if you will.”

Alexander Nee ’15 spent the summer of 2014 working with Associate Professor Mitchell Anthamatten on green synthesis of organic small molecule glasses for use in drug delivery platforms and gas membranes. Nee was initially frustrated by his slow progress -- until he was reassured by Anthamatten that he should not expect to come up with a groundbreaking discovery in two months time. “The thing I learned about research is that a lot of it is just discovering little things, and if you can quantify those little things you can give that to someone else,” said Nee.“Sometimes it’s just as important to find out that something doesn’t work, so somebody else doesn’t have to.”

Students apply for projects proposed by faculty members covering different phases of chemical engineering, ranging from applied to fundamental problems. The 10 or so students who are accepted work full time on their projects for 11 weeks, receiving $3,000 in remuneration.

And it is all possible because of Eisenberg, a Rochester native and self-described “do-it-yourselfer” who earned his B.S. in mechanical engineering and M.S. in metallurgy at the University of Rochester, then stayed on as an assistant professor in Mechanical Engineering. He joined the Department of Chemical Engineering in 1961, continuing as a professor emeritus after his retirement in 1983.

A six-footer who kept in shape playing squash with faculty associates, Eisenberg dedicated himself to undergraduate teaching, and also served as an industrial consultant to companies around the world.

He served as University marshal for more than 15 years; as an advisor to Tau Beta Pi, the engineering honor society, for more than 35 years; and was director of graduate students for what was then the University College of Liberal and Applied Studies for a decade and a half.

“One of the more valuable lessons I learned is that theory doesn’t always give you the answer to a problem,” Eisenberg explained. “Sometimes there are better answers you can get from common sense and practical considerations.”

Thanks to the fellowships he endowed, plus funding by the department and corporate sponsors, students in the Department of Chemical Engineering have a chance to learn that lesson firsthand.

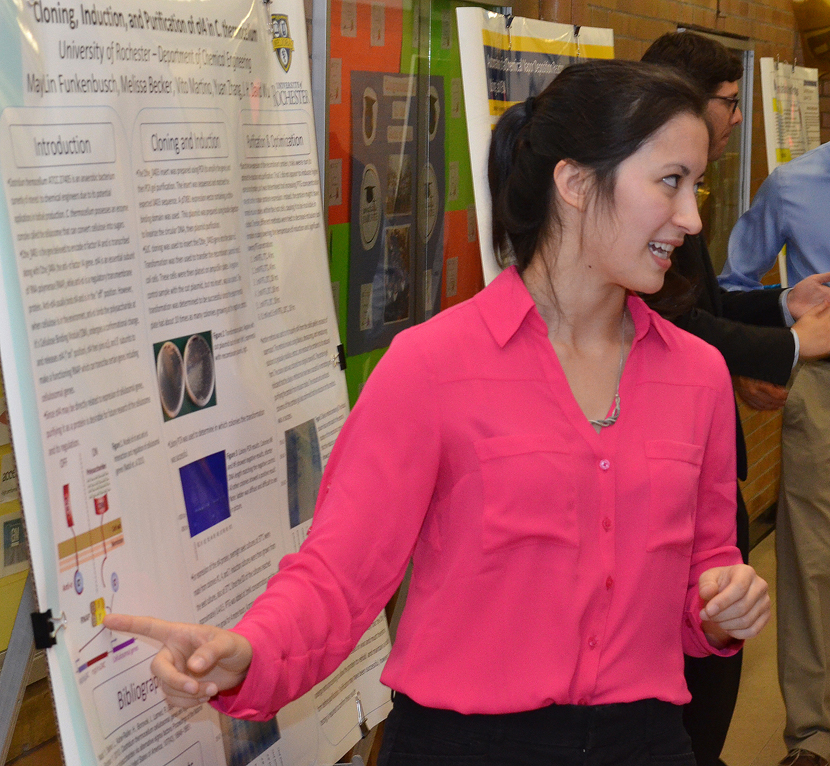

MayLin Funkenbusch ‘16, one of this year’s Eisenberg Research Fellows, worked on “Cloning, Induction, and Purifcation of oI4 in C. thermocellum” under the mentorship of Prof. David Wu. The Eisenberg program gave her an opportunity to compare research in academia versus research in industry, which she conducted the previous summer at Xerox.